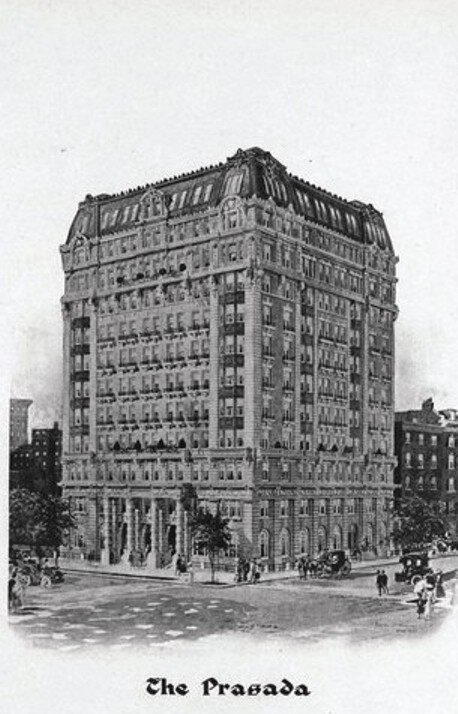

The Century at 25 Central Park West

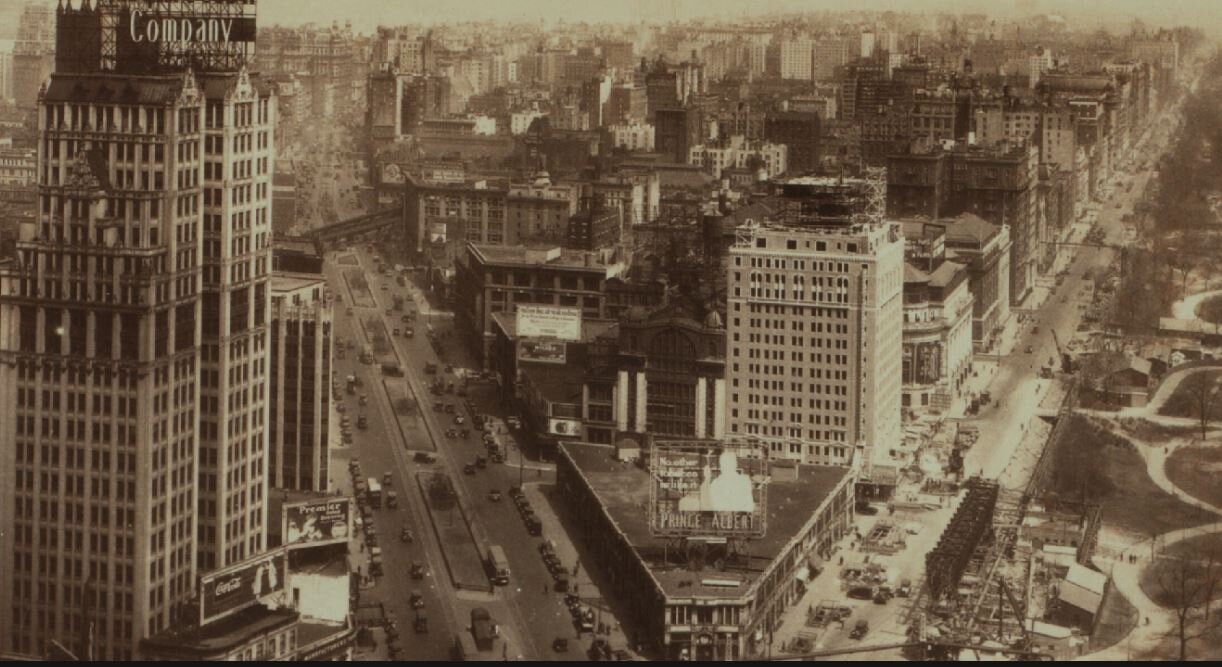

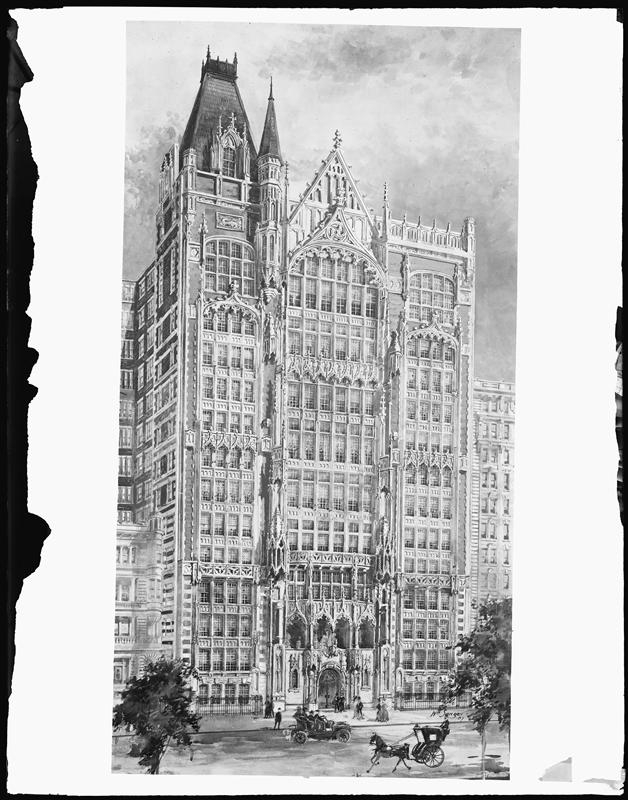

Can you name the four twin-towers of Central Park West? Beginning from the North, they are the Eldorado at 90th-91st Street, the San Remo at 74th-75th, the Majestic at 71st-72nd and the Century at 62nd-63rd.. These hi-rise towers, built between 1929 and 1931, transformed the skyline of the Upper West Side by more than doubling the height of all the existing buildings. They came about as a result of the Multiple Dwelling Law passed by the New York State Legislature in 1929. This law mandated an increase in yard and court area, but allowed residential buildings to rise higher than before, legalizing setbacks and towers that could span up to three times the width of the street on plots over 25,000 square feet. The last of these four buildings to be erected was the Century, constructed by the Chanin Construction Company, one of NYC’s leading builders and pioneers in the design of Art Deco buildings in America.

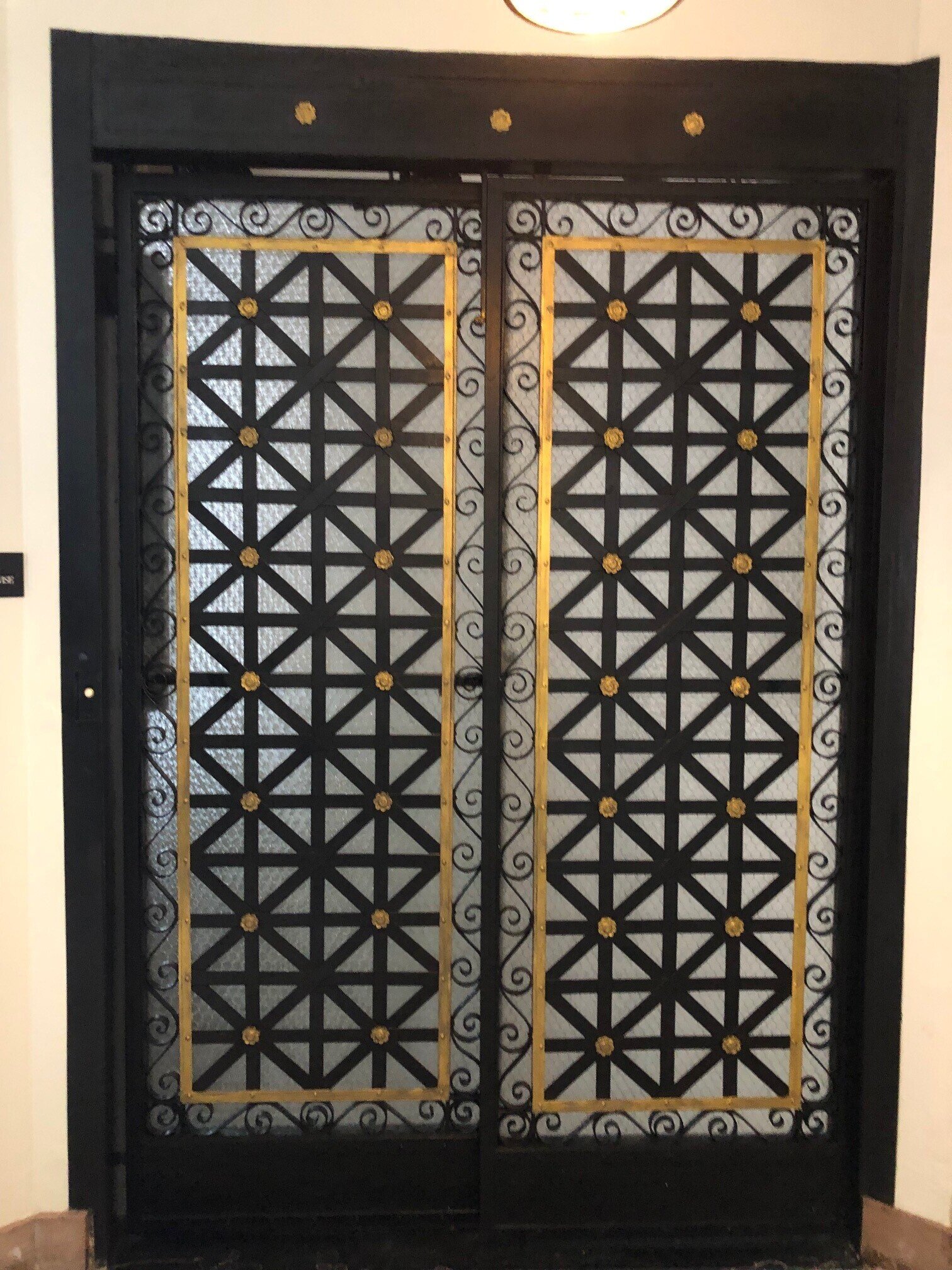

25 Central Park West Entrance

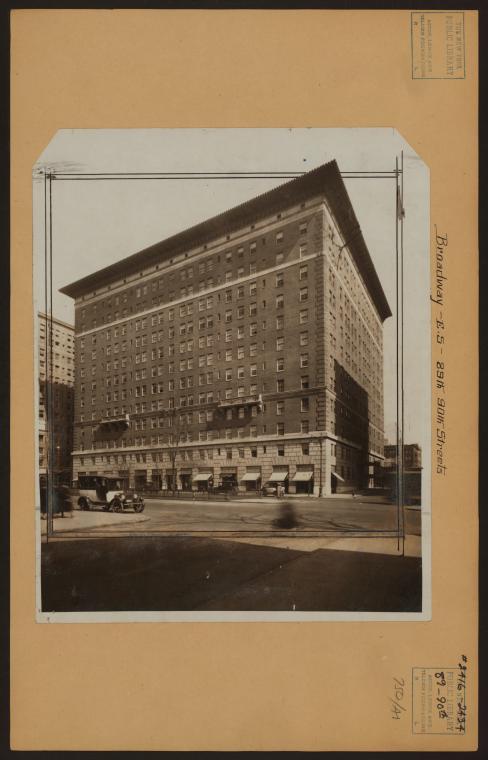

Irwin S. Chanin graduated from Cooper Union in 1915 with a degree in Civil Engineering and began his career as a builder and developer with his brother, Henry. Some of their early notable buildings include: the Fur Center Building (1924), the Chanin Building (1927) and the Lincoln Plaza Hotel (1928 - now Row NYC Hotel), all located in midtown Manhattan. They were also very prolific in the development of theatres. Beginning in 1925, they hired architect, Herbert Krapp, to design six Broadway locations, the 46th Street (now the Richard Rodgers Theatre), the Biltmore (now the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre), the Mansfield (now the Brooks Atkinson), the Masque (now the John Golden Theatre), the Royale (now the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre) and the Majestic Theatre. They also built several movie theaters including the Beacon Theater on Broadway and 74th Street which was restored in 2009 and is now one of New York’s leading live music venues currently under the management of Madison Square Garden.

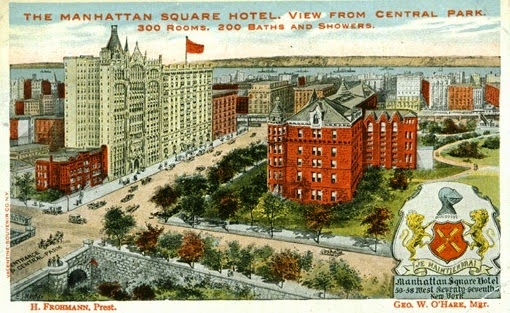

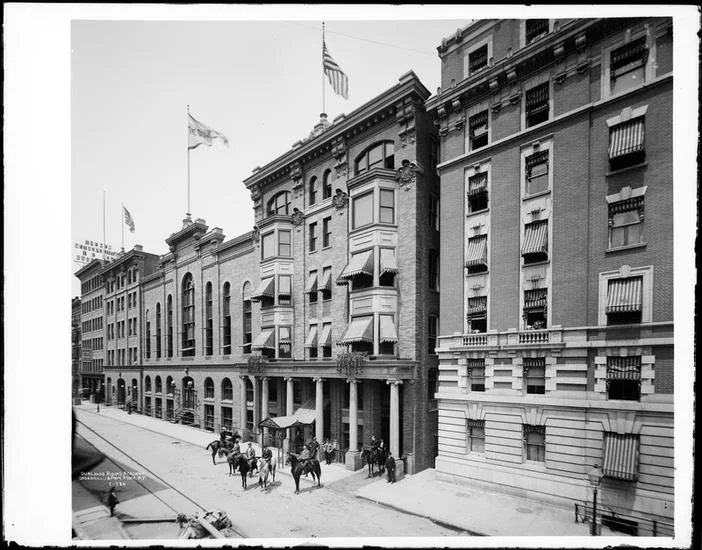

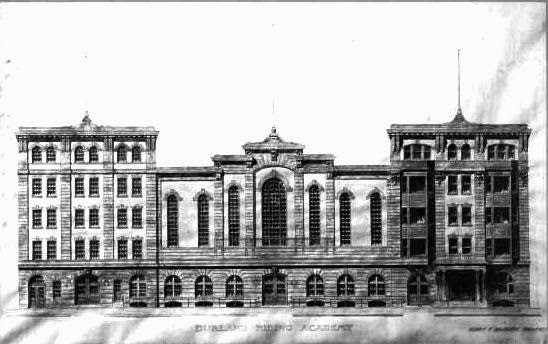

In 1929, the Chanin Construction Company purchased the entire city block bounded by Broadway, Central Park West, West 62nd and West 63rd Street. The site included the Century Theatre (1909) on Central Park West, Daly’s Theatre on 63rd Street and an apartment house and two garages on Broadway. As part of the agreement to acquire the Century Theater, which was then owned by the Schubert Organization, the Chanins were forced to sell them their interests in the Royale, the Masque and the Majestic Theatres.

The original plan to build a 65-story skyscraper quickly fell apart and it was decided that a second Art Deco inspired twin-tower building would join the Chanin’s Majestic, already being constructing several blocks to the north. By this time, Irwin Chanin had become a registered architect and worked on the design of both of these buildings. Although at first glance, the exteriors are fairly similar, he considered the Century to be a finer work, with the addition of more complex ornamental crowns on the towers and improvements to the design of the façade and windows. One of the other notable differences was the Century’s heavy concentration of smaller apartments, as larger units were becoming difficult to rent due to the Depression. Over the years, the building had its fair share of famous tenants including Ethel Merman, Jack Dempsey, Robert Goulet, Joey Heatherton and Nanette Fabray.

After a long and contentious battle, the Century successfully converted to a condominium in 1989. To this day, it is one of only three condos on Central Park West south of 88th Street, the others are 15 Central Park West and Trump International at 1 CPW. Some of the apartments have spectacular views of Central Park and many retain their original pre-war details and special features like sunken drawing rooms with fireplaces, duplex suites, creak-proof walnut and select hardwood floors and luxurious bathrooms with stand-alone showers. Irwin Chanin lived in the Century until his death in 1988 at the age of 96.

The Century was designated a landmark by the Landmark Preservation Commission in 1985.

View of Central Park West Looking North

If you enjoyed this post, please feel free to share.

If you’d like to subscribe to my blog and receive notification of future posts, please select SUBSCRIBE from the pull-down menu above.

If you’d like to know more about me and my listings at Brown Harris Steven, please select REAL ESTATE from the pull-down above or CLICK HERE or Visit: https://www.bhsusa.com/real-estate-agent/pamela-ajhar

Pamela Ajhar